The most dangerous sound in your business is silence

You are sitting in your weekly status meeting. The projector is humming and the slides are up on the screen. You look around the table at your team. You ask a simple question regarding the timeline for the new product launch or the status of the client integration.

Is everything on track?

Heads nod. There is a chorus of yes. The spreadsheet shows green cells. You feel a sense of relief wash over you. The plan is working. You wrap up the meeting and go back to your office to focus on the next quarter.

Two weeks later, the project implodes.

The deadline is missed. The client is furious. The code is broken. And as you scramble to put out the fire, you discover something that keeps you awake for nights afterward. You find out that your team knew about the problem a month ago.

They knew the timeline was impossible. They knew the software had a critical bug. They knew the client was unhappy.

But nobody said a word.

This is the nightmare scenario for every business owner and manager. It is not the crisis itself that hurts the most. It is the realization that you were operating in a reality distortion field. You were making decisions based on data that was fundamentally incorrect.

Why does this happen?

Why would people who care about their jobs and the success of the company stay silent while the ship steers toward an iceberg?

The answer lies in the mechanics of human hierarchy and the invisible friction that stops bad news from traveling upward.

The illusion of the open door

Most managers believe they are approachable. You probably have an open door policy. You have told your team repeatedly that they can come to you with anything. You genuinely believe that you are a safe person to talk to.

But there is a flaw in this logic.

An open door policy is a passive mechanism. It places 100 percent of the burden of social risk on the employee. It requires a subordinate to walk past their peers, knock on the door of the person who controls their salary and their career future, and deliver negative information.

Biologically, this is terrifying.

Our brains are wired to please authority figures. In our evolutionary past, upsetting the leader of the tribe could mean exile or death. That survival instinct is still active in your modern office. The brain perceives bringing bad news as a threat to survival.

So when you ask a room full of people if everything is okay, the path of least resistance is to nod. It is safer to hope the problem fixes itself than to be the one to ring the alarm bell.

We need to stop relying on passive openness. We need to actively architect systems that pull the truth to the surface.

The physics of information flow

Information in a hierarchy behaves like gravity. It flows down easily. Orders, vision, and strategy cascade from the top to the bottom with very little friction. But information trying to flow up has to fight against gravity. It has to fight against fear, against the desire to look competent, and against the worry of disappointing the boss.

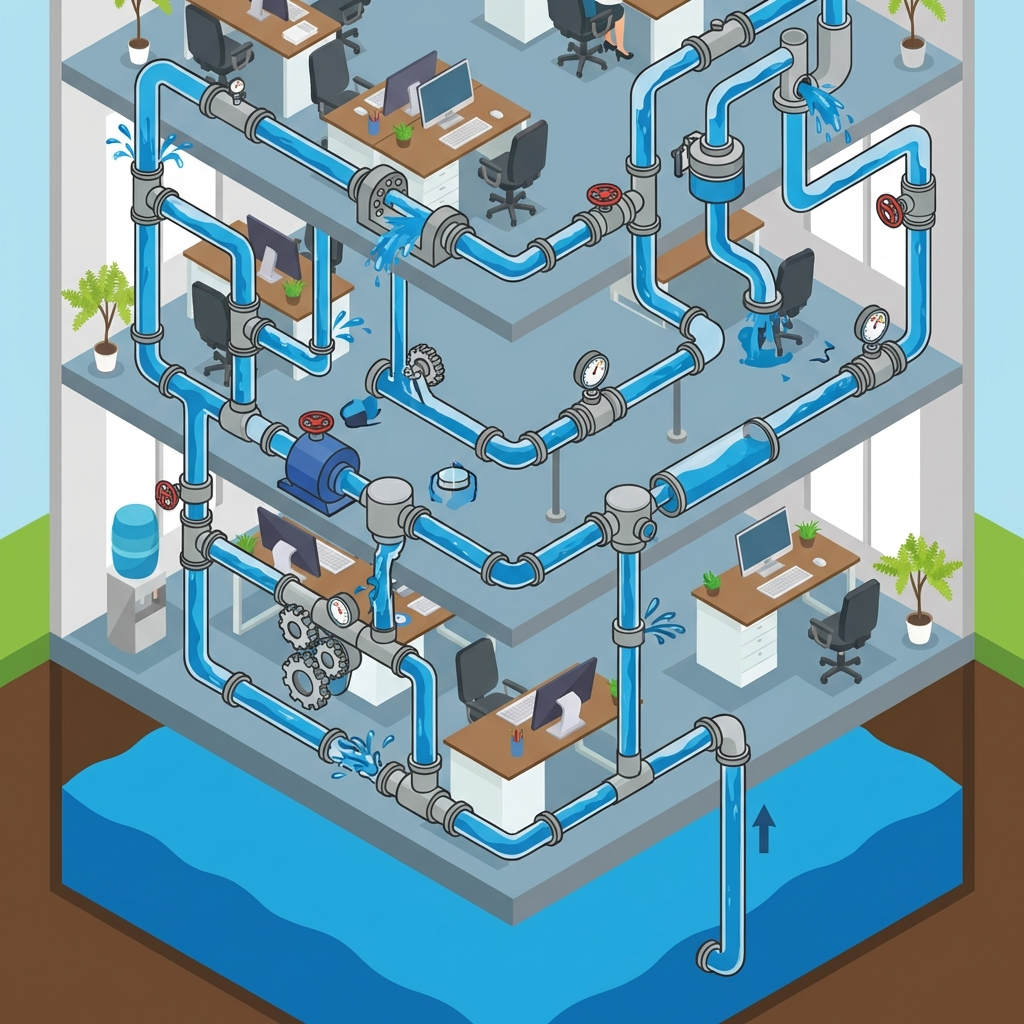

Furthermore, as information travels up, it gets filtered.

Imagine a customer support agent realizes a feature is confusing. They tell their manager. That manager does not want to look like their team is failing, so they soften the message before telling the director. The director softens it further before telling you.

By the time the signal reaches your desk, a screaming red alarm has been converted into a polite suggestion that we might want to look at something eventually.

This is called signal degradation.

To fix this, you must build bypass loops. You need channels that allow raw data to skip the middle layers of filtration and land directly in front of you without the messenger fearing for their life.

Architecting the feedback loop

So how do we actually build these channels? It requires more than just intention. It requires structure.

One of the most effective tools is the specific, scheduled request for friction.

Instead of asking general questions like ‘How is it going?’, which invites a generic ‘Fine’, you need to ask questions that presuppose a problem exists.

Try asking this: What is the one thing that is going to cause us to miss our deadline next month?

Or try this: If you were the CEO for a day, what is the first policy you would eliminate?

When you frame the question this way, you are giving permission to speak about the negative. You are framing the problem-spotting as an act of competence, not an act of complaining.

Another powerful mechanism is the concept of the ‘Pre-mortem’.

Before a big project kicks off, gather the team. Tell them to close their eyes and imagine it is six months in the future. The project has failed spectacularly. It is a total disaster.

Now ask them: Why did it fail?

Write down every reason they give. By moving the failure to a hypothetical past, you remove the fear. They are not criticizing the current plan; they are participating in a creative exercise. But the data you get from this meeting will be the most honest risk assessment you will ever receive.

The reaction is the product

Here is the most critical variable in this entire equation. It is not how you ask for feedback. It is how you react when you get it.

Your reaction to bad news dictates whether you will ever get bad news again.

Imagine an employee gathers the courage to tell you that a process is broken. They are nervous. They speak up.

If you sigh, roll your eyes, get defensive, or immediately start explaining why the process is the way it is, you have just killed the feedback loop. You have trained that employee that speaking up results in pain.

Even if you do not mean to, your micro-expressions matter. If you look stressed or angry, they will associate the truth with your anger.

You must train yourself to treat bad news as a gift.

When someone tells you something is wrong, your immediate response must be gratitude. You have to thank them for the visibility. You have to reward the messenger.

‘Thank you for telling me that. I would rather know now than later. That took guts to bring up.’

If the team sees that bringing you ugly problems results in praise and collaborative problem solving rather than blame, the floodgates will open. You will suddenly find yourself awash in information. This might feel overwhelming at first, but it is much better than the silence of the blind.

Institutionalizing the check-in

We cannot rely on these conversations happening organically by the water cooler. We need to schedule them.

Consider implementing ‘Skip Level’ meetings. This is where you meet with employees who report to your direct reports. You skip a layer of management.

The goal of these meetings is not to spy on your managers. It is to get a ground-level view of the reality. Ask them what their day-to-day frustrations are. Ask them what tools they are missing.

This does two things. First, it gives you raw data. Second, it signals to the entire organization that the leadership is interested in the reality of the work, not just the polished reports.

Another method is the anonymous pulse survey. But be careful here. Surveys are dangerous if you do not act on them.

If you ask people what is wrong, they tell you, and then nothing changes, you have just bred cynicism. If you use a survey, you must commit to publicly addressing the results, even the painful ones. You have to stand up in front of the team and say, ‘We heard you say X, and here is what we are going to do about it.’

The comfort of the truth

There is a fear that if we open these channels, we will be inundated with negativity. We worry that it will be distracting or demoralizing.

But consider the alternative.

The alternative is driving a car with a blacked-out windshield, hoping you do not hit a wall.

When you build a culture where feedback loops function correctly, the anxiety of leadership actually decreases. You no longer have to lay awake at night wondering what you are missing. You know that if there was a fire, someone would tell you.

You are building a sensor network for your business.

It allows you to fix small problems before they become company-ending disasters. It builds trust because your team sees that you are not delusional. They see that you are grounded in the same reality they are living in.

This takes work. It requires you to regulate your own emotions and to create safety for others. But the result is a business that is resilient, agile, and honest.

Don’t wait for the explosion. Go find the fuse.