The silent killer of your company speed: How to survive your own growth

Do you remember the early days?

Maybe it was just you and a co-founder in a garage, or perhaps a small team in a cramped office. You moved fast. If you had an idea at 9 AM, it was live on the website by noon. If a customer had a complaint, you fixed it yourself and sent them a personal email. There were no meetings about meetings. There were no approval forms. There was just action.

But then, you succeeded.

You hired more people. You signed bigger contracts. You opened new offices. And slowly, imperceptibly, the atmosphere changed.

Now, if you want to change a line of copy on the website, it requires a ticket in the project management system. If you want to buy a piece of software, you need three signatures. You look around at your thriving business and you realize that while you have more resources than ever, you feel slower than you did when you were broke.

This is the paradox of growth.

We strive for scale because we want to have a bigger impact. But the very mechanisms we use to manage that scale often destroy the agility that made us successful in the first place. We trade speed for control. We trade intuition for procedure.

This phenomenon is often called Process Paralysis. It is the creeping sensation that the organization exists to serve its own internal rules rather than the customer.

But here is the question we need to wrestle with. Is this inevitable? Is the destiny of every successful startup to eventually become a sluggish bureaucracy? Or is there a way to build a scaffold that supports growth without becoming a cage?

The anatomy of scar tissue

To understand why organizations slow down, we have to look at where processes come from. Very few managers wake up in the morning and think, ‘I want to make my team miserable today by adding a twelve-step approval process.’

Processes are almost always well-intentioned. More specifically, processes are usually organizational scar tissue.

Here is how it happens.

Three years ago, someone on the sales team made a promise to a client that the engineering team could not deliver. It caused a massive headache. We lost money. We looked bad.

So, in the aftermath of that pain, leadership made a rule. ‘From now on, no sales contracts go out without engineering approval.’

- It makes perfect sense.

- It solves the immediate problem.

- It prevents that specific pain from happening again.

But multiply that by five years of operation. You have a rule for the time someone lost a receipt. You have a rule for the time someone posted the wrong thing on social media. You have a rule for the time a laptop was stolen.

Layer by layer, you cover your organization in defensive armor.

The problem is that while armor protects you from getting hurt, it also makes it very difficult to move.

We need to ask ourselves if we are building processes to help us win, or if we are building processes to ensure we never lose. Those are two very different objectives. A team playing not to lose moves slowly and cautiously. A team playing to win moves with calculated aggression.

When you look at your current handbook or your operations manual, how much of it is designed to create value, and how much of it is designed to prevent a mistake that happened once in 2019?

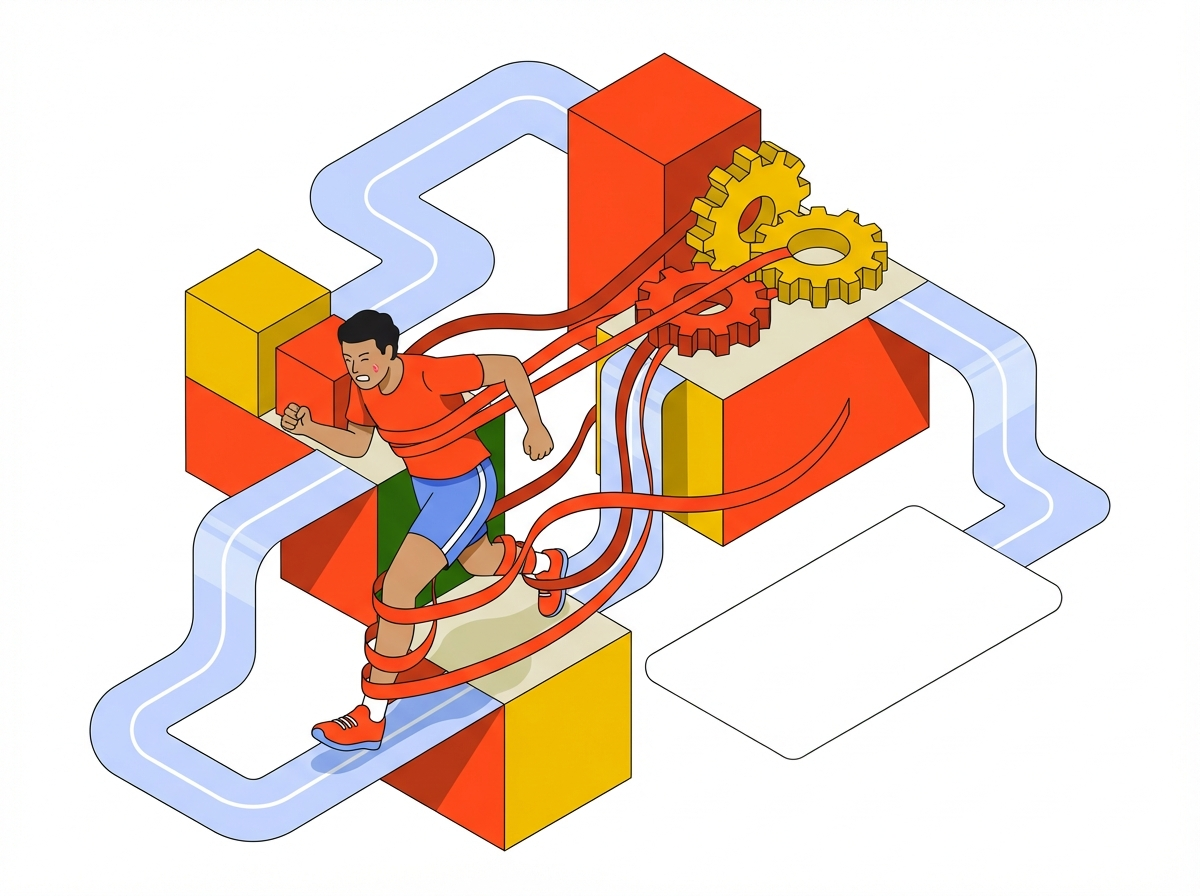

Guardrails versus Gates

This brings us to a critical distinction in how we structure our businesses. We need to distinguish between guardrails and gates.

A gate is a stoppage. It is a point in the workflow where activity ceases until a person of higher authority grants permission to proceed. The engineering approval on the sales contract is a gate. The manager signing off on an expense report is a gate.

Gates are expensive. They cost time. They break flow. But most damagingly, they erode agency. Every time an employee hits a gate, they receive a subtle psychological signal: ‘We do not trust your judgment.’

Guardrails are different.

A guardrail is a constraint that allows for speed within a safe zone.

Think about a highway. The guardrail does not stop the car. It does not force the driver to pull over and ask for permission to keep driving. It simply defines the edges of the road. As long as the driver stays between the lines, they can go as fast as they want.

In a business context, a guardrail looks like this: ‘You can spend up to $500 on any tool that helps you do your job without asking anyone, provided you put the receipt in this folder.’

That is a guardrail. It sets a boundary (financial risk is capped at $500) but within that boundary, it grants total autonomy.

The shift from a gate-based culture to a guardrail-based culture is terrifying for many managers. It requires a relinquishing of control. It means accepting that people might make mistakes.

But the ROI on that risk is speed. When your team knows the boundaries, they can sprint. They don’t have to look over their shoulder every ten yards to ask if they are going the right way.

The cognitive load of compliance

There is a hidden cost to process that does not show up on the profit and loss statement. It is the cognitive load required to navigate the bureaucracy.

Every time a talented employee has to pause their actual work—the coding, the designing, the selling—to figure out which form to fill out or whose calendar they need to get on for an approval, they are burning mental energy.

Human cognitive capacity is finite. We only have so many hours of deep focus in a day.

If your organization requires 30 percent of that mental energy just to navigate internal compliance, you are getting 30 percent less innovation. You are paying for 100 percent of a brain but only utilizing 70 percent of it because the rest is occupied with administrative navigation.

This is why high-performers leave big companies.

They do not leave because the work is too hard. They leave because the work is too hard to get to. They get tired of fighting the internal war just to have the privilege of doing the job they were hired to do.

When we are designing our workflows, we have to treat cognitive friction as a serious defect. A confusing process is just as bad as a broken product.

The concept of the Sunset Clause

So how do we fix this? We cannot just burn the rulebook. We do need structure. We do need compliance, especially in regulated industries.

The solution is to treat your processes like you treat your products. They need to be iterated on, and sometimes, they need to be discontinued.

In law, there is a concept called a Sunset Clause. It is a provision in a statute that states the law will cease to have effect after a specific date, unless further legislative action is taken to extend it.

Imagine applying this to your company policies.

What if every new rule came with an expiration date?

When you implement that new approval workflow for marketing assets, you agree that it expires in six months. In six months, the team has to meet and vote on whether to renew it.

This changes the default state. In most companies, a rule lives forever until someone fights to kill it. With a Sunset Clause, the rule dies automatically unless someone fights to keep it.

This forces a regular audit of your organizational complexity. It forces you to ask: ‘Is this rule still serving us? Does the risk this rule prevents still exist? Is the cost of this process worth the safety it provides?’

You will be amazed at how many processes simply vanish because nobody cares enough to renew them. If nobody fights for the rule, the rule was probably just red tape.

Building for the exceptions

There is one final trap that leads to paralysis. It is the tendency to build processes for the 1 percent of bad actors rather than the 99 percent of good ones.

We often design our entire expense policy because one guy five years ago tried to expense a family vacation. We design our entire remote work policy because one person abused the privilege and didn’t work.

When you build for the exception, you punish the majority.

You are telling your 99 hard-working, honest employees that you do not trust them because of what one person did. This creates a culture of low trust, and low trust is slow.

Speed happens at the speed of trust.

If you trust your people, you can move fast. If you have to verify everything they do, you will move at a snail’s pace.

It is often cheaper to accept the occasional loss—the occasional bad expense, the occasional mistake—than it is to pay the tax of trying to prevent every single error.

The goal is not perfection. The goal is net forward momentum.

The continuous garden

Your business is not a building. You do not build the structure once and then live in it.

Your business is a garden. It is a living, breathing ecosystem. Processes are the trellis that helps the plants grow upward. But if you have too many trellises and not enough plant, you just have a pile of wood.

Or if the vines act like kudzu and choke out the light, the garden dies.

As a leader, your job is not just to plant the seeds. Your job is to prune. You have to walk through the garden of your organization with a pair of shears, looking for the overgrowth. You have to look for the processes that are choking the life out of your team.

It is scary to cut. It feels safer to leave the rules in place.

But if you want to build something that lasts, something that retains the soul of a startup even as it reaches the scale of an enterprise, you have to be vigilant.

You have to fight for simplicity. You have to fight for speed. And most importantly, you have to trust the people you hired enough to get out of their way.